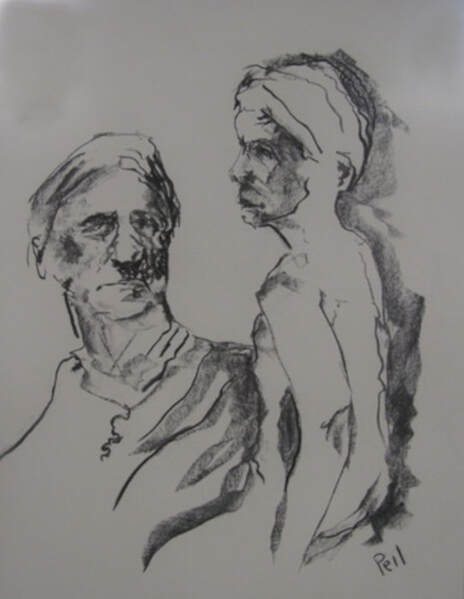

David Pell

|

I came to art by way of painting scenery for the Little Broadway Marionette Theater, the puppet theater I had as a child and teenager. In high school I studied oil painting with Irondequoit artist Annette Raphael, student of Fritz Trautman, who has a painting in the Memorial Art Gallery, who in turn studied with Abstract Expressionist painter/teacher Hans Hofmann.

In college I took a ghastly studio art class where I learned nothing. For more than twenty years I made no art until one day I wanted again the experience of smelling linseed oil. I am a figurative artist, working in oil, charcoal, and Conté crayon. Neither of my parents and none of my grandparents were artistic: I figure I must be a mutation. |

I think of myself as a medium or channel: being able to draw and paint is a gift. I don’t really know why I can draw and paint. Light hits a face, bounces off and goes into my eyes; electrical messages travel from my retina to my brain, and my mind thinks “That face is beautiful.” More electrical signals come down my arm to my hand and fingers and I move them and marks appear on paper. To me, how this happens is an incredible mystery.

Like so many artists in the past hundred years, I admire Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), the “Father of Modern Art”; he is a great inspiration. Ten years ago I read everything I could about him and looked at as many of his paintings and drawings as I could. During Cézanne’s life, the public and many of the critics reviled his figures. Critics wrote: “Is that a foot or a hand?”—“Breasts, bellies, buttocks—grossly exaggerated.”—“Vulgar!”—“Ugly people!”—“Morbid nudes, lewd and swollen.”—“Immoral!”—“Demented!”—“Dislocated limbs.”—“Crooked eyes.”—“Deformed horrific bodies!”—“Obscene!”—“Skin suffering from eczema.”—“What happened to their faces?”—“The figures have no faces.”—“Is that a boy or a girl? Part male, part female?”—“Nude people don’t look like that!”

An art critic in a video documentary about Cézanne said, “Cézanne was able to suggest to those who were willing to hear that from now on you could do anything you like in painting. He freed the possibility of reinventing the figure. I propose that Cézanne has left his mark on everyone in this century.”

But Cézanne was a very neurotic control freak: when a painting didn’t turn out exactly as he wanted, he’d break brushes, tip over the easel, slash the canvas and stomp on it.

I learned from this bad example not to try to control how my drawings or paintings progress and eventually turn out. When I start to draw or paint a face, as a springboard for structure I use one of the Xeroxes of faces from my collection. (Embarrassed to be around nude models, Cézanne used women’s fashion catalogs as a guide for creating his figures.) After a structure emerges, about halfway through the work, I let the face in the artwork tell me what to do. I try to interact with the face that is appearing. I don’t set out to capture a particular emotion; during the drawing and painting the emotion reveals itself. If I’m not surprised, why would anyone else be interested?

Making straight lines and detail work drives me nuts. I keep my style loose and believe in making random marks, which frequently turn out more meaningful and suggestive than any premeditated marks.

If you want to learn more, go to the library! Look at art books, read about technique. Experiment and practice!

I am a member of the New York Figure Study Guild and the Rochester Art Club.

Here are two quotations from Cézanne:

Like so many artists in the past hundred years, I admire Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), the “Father of Modern Art”; he is a great inspiration. Ten years ago I read everything I could about him and looked at as many of his paintings and drawings as I could. During Cézanne’s life, the public and many of the critics reviled his figures. Critics wrote: “Is that a foot or a hand?”—“Breasts, bellies, buttocks—grossly exaggerated.”—“Vulgar!”—“Ugly people!”—“Morbid nudes, lewd and swollen.”—“Immoral!”—“Demented!”—“Dislocated limbs.”—“Crooked eyes.”—“Deformed horrific bodies!”—“Obscene!”—“Skin suffering from eczema.”—“What happened to their faces?”—“The figures have no faces.”—“Is that a boy or a girl? Part male, part female?”—“Nude people don’t look like that!”

An art critic in a video documentary about Cézanne said, “Cézanne was able to suggest to those who were willing to hear that from now on you could do anything you like in painting. He freed the possibility of reinventing the figure. I propose that Cézanne has left his mark on everyone in this century.”

But Cézanne was a very neurotic control freak: when a painting didn’t turn out exactly as he wanted, he’d break brushes, tip over the easel, slash the canvas and stomp on it.

I learned from this bad example not to try to control how my drawings or paintings progress and eventually turn out. When I start to draw or paint a face, as a springboard for structure I use one of the Xeroxes of faces from my collection. (Embarrassed to be around nude models, Cézanne used women’s fashion catalogs as a guide for creating his figures.) After a structure emerges, about halfway through the work, I let the face in the artwork tell me what to do. I try to interact with the face that is appearing. I don’t set out to capture a particular emotion; during the drawing and painting the emotion reveals itself. If I’m not surprised, why would anyone else be interested?

Making straight lines and detail work drives me nuts. I keep my style loose and believe in making random marks, which frequently turn out more meaningful and suggestive than any premeditated marks.

If you want to learn more, go to the library! Look at art books, read about technique. Experiment and practice!

I am a member of the New York Figure Study Guild and the Rochester Art Club.

Here are two quotations from Cézanne:

“If I think while I’m painting, if I get in the way, then everything collapses.”

“Study, meditation, joy, sorrow—these are the preparations for painting.”

“Study, meditation, joy, sorrow—these are the preparations for painting.”

Someone asked me, “So art is sort of a hobby for you?” I didn’t know what to say and shrugged. The person said, “You know, a hobby,” and because a response seemed to be needed, I said, “Well, I don’t support myself as an artist.” I should have said, “Art supports me. Drawing and painting give meaning to my life, in the face of an otherwise chaotic and meaningless world.